In different parts of Philadelphia, two women of the same age receive news they’ve been anxiously awaiting…they are pregnant.

They both dream about baby names, nursery decorations, tiny outfits and stylish diaper bags as they progress through their pregnancies.

Nine months later, one mother gives birth to a healthy, thriving baby girl. The other mother continues on her daily trudge to the intensive care nursery to visit her baby; born three months premature.

The only difference between these women is their race; one is white and the other is African-American.

This dichotomy occurs repeatedly throughout the country and unfortunately racial differences continue to have a major impact on pregnancy outcomes. According to the March of Dimes, African-American women are three times more likely to give birth to a premature baby than white women.

Premature birth results in a multitude of medical and financial challenges for the families in which it occurs. Children who are born premature often experience cardiovascular challenges, respiratory problems, issues with digestion and developmental delays, which often require years of specialized therapy and treatments. The financial ramifications of premature birth are just as overwhelming. The Center for Healthcare Research and Transformation at the University of Michigan reports that the average charge per discharge for premature birth and low birth weight was $119,389 in the U.S., and families are often responsible for a large portion of those fees, as well as fees incurred from the continued care for the premature child.

Preterm Birth Philadelphia 2010

*Data taken from Philadelphia Department of Vital Statistics

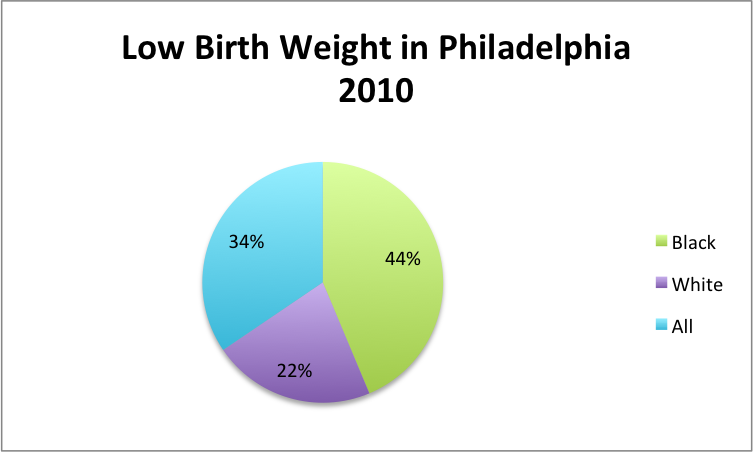

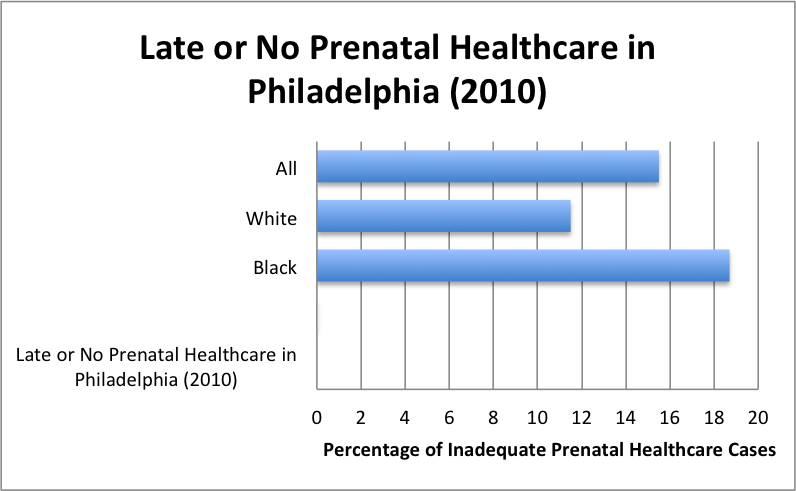

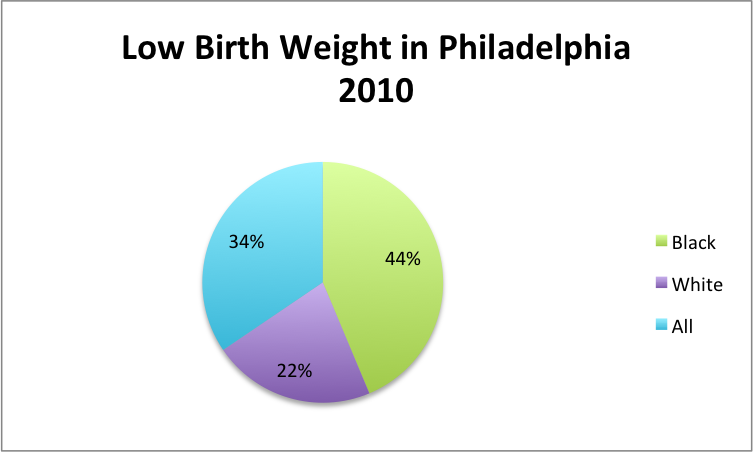

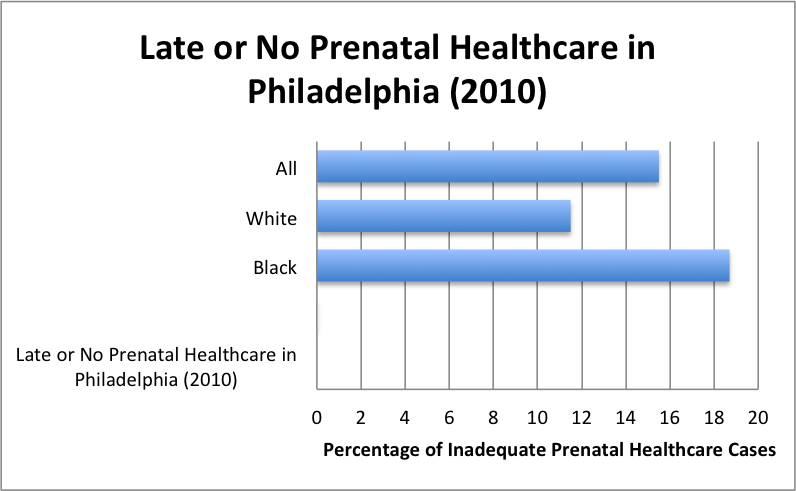

This issue is further compounded in the African-American community by the fact that many mothers in this demographic are considered lower-income, and have limited access to quality prenatal healthcare. In Philadelphia, where the African-American population is around 44%, this disparity results in substantially increased rates of premature birth in the community, in fact the rate of African-American babies born prematurely has continued at a rate of 40% higher than whites in the city. In addition, African-American women are almost 50% less likely to have adequate prenatal care, and are twice as likely to deliver a low birth-weight baby.

Low Birth Weight Philly

*Data taken from Philadelphia Department of Vital Statistics

Several organizations are engaged in researching this disparity, most notably, the March of Dimes. Dolores Smith, the Program Director for the Southeastern Pennsylvania chapter of the organization says that there are two main areas where racial differences are clearly manifested in prenatal care and childbirth; the biological differences between African-American and white mothers and the socioeconomic differences that exist between the two groups.

“When talking about the biological factors or genetic factors, we know that African Americans have higher rates of certain diseases like hypertension, cardiac disease, and diabetes. Just like the heart, the uterus is a muscle and is affected by these conditions too, and even more so during pregnancy. This is one reason why we see a higher rate of prematurity in the African-American community” She says.

Smith also recognizes the impact that socioeconomic differences have on premature birth.

“We’ve understood for a while that African-American mothers have disproportionately lower access to prenatal healthcare, and we continue to work to change that disparity. However, there is a considerable amount of research out now that postulates about how the stress of racism and discrimination can result in negative birth outcomes as well,” she says.

In a recent study conducted jointly between Northwestern University and Children’s Memorial Hospital, researchers found that women who experienced discrimination were more than two times as likely to deliver a premature baby. While the mechanisms that cause the premature birth after discrimination are varied, it is clear from the study that simply providing adequate prenatal care is not enough to solve the problem of prematurity in the African-American community.

Rachel Thompson, a former patient at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital’s Prematurity prevention program believes improvement in prematurity disparity is possible.

She says, “I had my first baby when I was seventeen and he came two months early, but when I had my second baby a few years ago, I was enrolled in the prematurity program at the hospital. She was born just a few weeks early, but I was prepared for that already. I felt like I had a group of people who really cared about me and the baby and I was not so alone. There are so many other women I know who needed a program like that and didn’t get it. I wonder what happened to them.”